A right frample

A selection of scribbles 1973-

may isle

CONTENTS

- Columns (60)

- Prose poems (24)

- Songs (14)

Welcome

Letting go

Heads, eyes and hands

Perfect spring

Choose who you trust

(I don’t want to leave) St Monans

Feeling a bit under the leather?

A little while back, while volunteering at our small local museum, a young family from abroad were intrigued by an exhibit, the likes of which they had never seen before.

It was a strip of

leather, with a shaped grip at one end and two prongs at the other. We know it as the ‘tawse’.

I’d also not

long finished Nanzie McLeod’s book, ‘Tales from the East Neuk’, where, in one

chapter, she describes the over-use of the ‘tawse’ and one teacher’s over-enthusiastic

application of it. It was actually a disturbing passage from a time where if a

child asked to go to the toilet, he or she would be permitted, but would be ‘belted’

on return. The option was to wet yourself and be spared the leather but then

endure the humiliation of your classmates watching you mop up your own puddle.

So a few days later there I was explaining to visitors, from a different country and generation, how this

‘tawse’ was used to punish children and was a common teaching accessory across

Scotland, only finally being banned in 1987.

Like most boys,

and some girls, I was belted at school. I wasn’t a frequent victim of the

punishment and, in my era, there were some who competed for the highest tally

as a masochistic badge of honour.

My mother had

been belted at school for ‘talking’ when it actually had not been her. The pupil

code of honour meant you could not incriminate a classmate, not that it

probably would have done any good, so she took her punishment and, while the

pain would have quickly subsided, the injustice endured for the rest of her

days.

I could sympathise

with that. Even though I could accept that most of the times I was belted I

had, according to the rules of the day, deserved it, my lingering personal memory

is the one unjust belting I received

Sitting quietly

in class, the lad behind me, who I believe had watched an episode of the Man

from UNCLE the evening before, decided to practise a Napoleon Solo karate chop

on me. My bare, unprepared neck suddenly took the full force of the side of my

classmate’s hand. I still remember the pins and needles that went through my

head and spine, all the way down to my toes, and the black mist that blurred my

eyes. The unexpected blow pushed me forward and I squealed in pain.

What was equally

unexpected was the lesson that came with this unprovoked attack. Apparently

uttering any sound when subjected to a full-force martial arts blow qualifies

as academic insolence. So with shaky knees, blurred vision, and tingling from

teeth to toe, I was yanked out in front of the class, the tawse was removed

from its tin box home, and I was given ‘two of the best’, screamed at, and

shoved back into my seat.

It was an unfair

punishment, but I saw many of these. Some linger as disturbing memories and while

many of my age will have similar tales to tell, even as a young child there

seemed something seriously wrong with a grown adult attacking as child with a

strip of thick leather.

At my primary

school you were spared the tawse until primary three, after that you were fair

game for a good leathering. So, by my reckoning, that would have been ages seven

and upwards. Without judging the overall

rights and wrongs of corporal punishment, in that era there was a case to be

made for the belt being used to curb bad or dangerous behaviour, but then there

were areas where you just have to ask, “What sort of adult could justify

inflicting pain on a child for THAT?”

Needing to go to

the toilet as described in Nanzie McLeod’s book, certainly falls into that

category, as does, ‘in my book’ failing to salute your teacher if you saw them

outwith school.

These two

example are just bizarre acts of cruelty and self-importance, but there was one

more instance, commonly accepted, where the belt was widely wielded and seen as

completely justified, and that was in academic performance.

In my school

days, it was humiliating enough for children to be seated according to their

abilities, there was the zone of terror associated with being ‘bottom of the

class’ and the teacher’s pets who occupied the lofty heights of being ‘top of

the class’.

I endured

neither of these pressures, being safely ensconced in the middle rankings, but

even as children we all felt there was something just not right about that ‘bottom

of the class’ ranking. It wasn’t a revolving role, those that occupied those

handful of seats rarely moved, and the tenant of that lowliest of desks was usually

a permanent resident.

As we moved into primary seven, around 40 of us, our teacher saw the belt not just as a means of punishment but as a vital teaching aid, one that could improve every aspect of your academic ability. It was a cure for dyslexia; it improved your understanding of arithmetic; it could help you spell; it could help you write quickly in dictation tests...

Where teaching failed and ability was restricted,

the solution was to inflict as much physical pain as you legally could on a

child, then it would all be good.

To this day, I

firmly believe that ‘Miss’ who stood in front of us should have been thrown out

the profession, charged with assault, and a restraining order imposed so she

was never allowed near a child again.

Harsh? I don’t think so. And I rest my case on the Friday

when all but one of us sat in silence and realised that what was unfolding in

front of our impressionable eyes was not just wrong, but cruel and demented.

Friday mornings became

our academic judgement day. We had a string of tests that began with mental

arithmetic, followed by spelling, then dictation (rapid long hand with correct

punctuation and spelling), then ‘problems’.

A certain number

of mistakes saw you being given extra class work as punishment. More sums to

do, correcting each spelling mistake by writing it correctly ten times, being

given extra dictation and extra homework etc.

Somewhere in her

warped perception of the world, Miss decided it would be an inspiring spectacle

for the rest of us if the worst performer in the class in each of these

subjects was belted – given a damn good thrashing.

Now, let’s call

him ‘Mossy’. He was a gentle wee soul, polite, always spotlessly turned out,

friendly, and a hard worker who always did as he was told. But try as he might,

and he did try, academically he needed help and support. He needed one-to-one teaching,

an adult whipping him with leather was not going to help. We all knew that,

except Miss.

So this one

Friday, Mossy flunked his metal arithmetic test badly, as he always did but

instead of being given extra sums, he was pulled out from behind his bottom-of-the-class

desk, and with his wee hand outstretched received four, or possibly six, of the

best, along with a good screaming from Miss about how stupid he was.

Sobbing, he was

shoved back into his seat, told to stop his snivelling, and the rest of us were

given a lecture on what would happen to us if we performed as badly as Mossy.

It was a

horrible sight to witness and created an atmosphere, not of fear because those

at the top end of the classroom knew they were never going to face that level

of punishment, ever. I remember it more of an unsettling mood; without speaking

we had witnessed something that was very wrong.

Then we moved on

to the spelling test.

I remember I got

a few wrong but Mossy failed miserably. And with tear stains on his face and

his hand bright red from the last belting, he was again positioned in front of

us and, crying with so much pain, he took another thrashing as the tawse repeatedly

came thundering down on him.

This just didn’t

make sense, and I don’t know if Miss, having made her threats at the start of

this Friday morning felt she had no option but to continue this bizarre

academic lesson.

Dictation was up next, and that was a subject

us middle-rankers had previously been screamed at over our performance. I still

don’t really understand its merit in a primary curriculum. In a shorthand

course, yes, but to have a teacher read out a passage and you try and take it

down in long hand, with no spelling or punctuation mistakes is a challenge. If

you struggled with a word, you would drop behind and forget what had been said.

There was always a chance you could submit a nearly blank page for marking.

That had happened in the past to Mossy, and it happened again.

So for a third

time, this wee lad, shouted at, insulted and pulled in front of the class, was expected

to take another belting.

By now he was

sobbing uncontrollably and, refusing to hold out his hand, he stuttered, “No Miss,

no, I’m no’ taking the belt again. I’m going home and tellin’ my mum and dad...”

At that he made

for the classroom door and had just got his hand on the handle when Miss

grabbed him. She started slapping him around the head so hard that he ended up

on the floor. By now she was apoplectic and dragged him out the classroom. In

the corridor outside we could hear her screeches and his sobs while the whacks

continued. Then he was apparently hauled up to the headmaster and, I believe on

account of his insolence, he was sent home.

Miss returned to

an unusually silent class. I have no recollection of anyone speaking at all,

certainly an unusual phenomenon when a teacher wasn’t present. It was as if we

all knew we had been witness to something unnatural.

I’m not sure but

I think because of the beltings and Mossy’s departure from school, we weren’t

given our problems’ test that Friday. That was a relief to all of us.

Did that mark

the end of the beltings, or the Friday nightmares? No, of course not, though I

don’t recall them ever being so uncontrolled again. Mossy was back at school

that Monday and life went on much as before with Miss sitting at her desk

sucking on a boiling while her belt lay coiled in that tin before her.

I don’t know the

long-term effect all these thrashings had on Mossy but they had a profound

effect on me.

When the next

visitor to the museum asks about the ‘tawse’ I won’t share this tale, but it

shouldn’t be forgotten. Lessons were certainly learned with all those beltings

from the tawse but the most important ones concern those hands that gripped it,

not those who waited to feel it.

Bills and wills at journey’s end

There is a weariness to my moods these days. It weighs most heavily when I take a backward glance at my past and it sits in my mind’s eye just for a few seconds alongside the present, like one of those ‘then and now’ photo features.

Like many folk, when I stopped earning, your state pension becomes a sharp reminder that life has changed and unexpected expenses you used to wince at before can now force a dramatic rethink on so many different aspects of your life.

When you are confronted with an unavoidable bill, you take the matter very seriously, weighing up what steps you will need to take before you start finding that all important tradesman. But that financial worry and anxiety is added to by the process of trying to find someone willing to take your money.

I’m sure it wasn’t always like this. We are facing a roof repair and I’m expecting this is not going to be a small change job. Over the past fortnight we have contacted a good number of firms, some more than once. Out of that total, only one has replied, and that was to say the job was of no interest.

My money is as good as the next person’s, so is business booming to such an extent that we have now gone from the capitalist dream of cost-effective competition to over-priced monopolies? Keeping the customer satisfied seems to be in the past, as does respecting those who trust you enough to hand over their hard-earned, or rationed, cash.

How, and when, did the world I once know change so much?

And that brings me to the real downer.

I’m not organised enough to plan decades ahead, and neither is my wife, so when the decision came to draw up our will and testament, it was one made in the shadow of human frailty and finality. Obviously, you hope this document will stay safely sealed for a long time to come but, realistically, we know it is something that needs doing… now.

On a personal level, a lawyer’s office is not a place I have frequented. I’ve had numerous professional engagements with the legal world but, on a personal face-to-face level, they have been very rare occasions.

The last time I visited our family’s legal firm, which seems to have been in operation since the days of quills and candles, had to be more than 20 years ago. Then it was with my mother and, if I remember correctly, something to do with deeds and, as was her wont, ensuring all her official paperwork was in order. A trait I never inherited.

I remember the visit clearly. The sparkling woodwork and fragrance of furniture polish. The clicking of keyboards, the atmosphere of quiet efficiency, the ambiance of a learned profession, aloof from the mundane modern world outside.

I didn’t find it intimidating, but reassuring. A world of knowledge, dignity and timeless decorum.

And decades later I was back, standing outside the door. All the shops in the street were locked up on this weekday afternoon, the brass name plaques needed polished, the door needed varnished, and it was locked. When we made the appointment we were warned we might have to knock.

The office seemed silent as the knock echoed through the building. There were no keyboards clicking, no telephones ringing, just silence.

It took a while but the solicitor duly unlocked the door and we stepped inside. It was empty; not just empty, it felt abandoned.

“Ah, Mr and Mrs Morkis,” said the solicitor. “I’ll be with you in a minute, please take a seat.”

He gestured to a small place under the staircase while he went of to fetch the necessary papers.

So this was it? Our will and testament, our final legal act while of sound mind. Signing off from our lives, and signing away all we had at the end of a journey we had made together.

This was the solemnity of the occasion. A small table covered by a plastic 'cloth', opposite a broken office chair, a rust-stained, leak-damaged radiator, under a flight of stairs, in an empty office.

When he returned with those all-important and pricey documents, word for word the same as my late mother’s but with my name instead of hers, I wasn’t expecting parchment but I have a heavier stock of copy paper from Home Bargains for my desktop printer.

We duly signed the pages and were ushered back out on to an empty street, and the door closed behind us, and on our lives, at least legally.

That was it.

I am made to feel of more value at a supermarket checkout. I don’t know what I expected, but it wasn’t that. Did I really expect to be treated differently from someone looking for legal representation for a forthcoming breach of the peace case? Yes, I did.

This was a solemn moment of finalising the paperwork that would act as the bridge between our deaths and those left behind. At least that how we both saw it. It was a jolt to realise we were just an irrelevant broken-down couple in a broken Britain.

It would have been more satisfying to scrawl my last wishes on the back of an abandoned cigarette packet while having a tea and a Kit Kat in a transport cafe.

As you get older, there are so many areas where you feel, or are made to feel, worthless and insignificant.

This was certainly one of them.

An unfortunate case of indecent exposure

My uncomfortable relationship with the alphabet

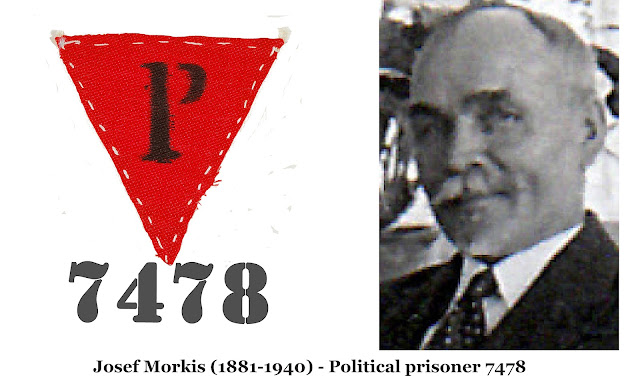

International Holocaust Day: Would you be wearing a badge?

‘Morning’... has broken

-

Continuing my solo therapy with there not being enough resources for a one-to-one with a professional, deemed not suitable for a group onl...

-

October 9, 2019 Have you ever sat in your car in a hospital car park, trying not to be sick; wanting not to have seen what you’ve s...

-

April 1973 Dressed up but messed up, standing four deep on London Road, trying to block the visions of hospital beds and muffle the ech...

-

Fife Free Press, January 9, 1997 A million words must be written every year about the commercialisation of Christmas; how the tru...

-

I’m in no doubt there must be a balance to our existence, a natural Hegelian dialectic on life. Where there is good there will be bad. It’s ...

-

December 16, 2018 In many areas of the newspaper industry, core design is now by means of template. To those not familiar with the p...

-

There is a Scottish saying, “We’re a’ Jock Thamson’s bairns”. Depending on your outlook on life that’s a very socialist, Christian, Buddhist...

-

1980 Time doesn't matter, there is no clock or calendar, just static scenery. Continuing galleries filled with all the people once k...

-

Fife Free Press, October 4, 1996 I think it's a male thing. While the average ‘guy’ is supposed to like his beer and his footb...

-

Johnston Press, Friday, June 26, 2015 Do you get today's newspaper delivered, or did you pick it up from the shop? In the vein of...