International Holocaust Day (January 27) has an even deeper and personal meaning for me this year.

Of course, it is a date that should make everyone pause, think and vow that the horrors of the 1930s and 1940s will never be repeated, but, of course, they have been. The roots of that ideology remain strong and the resulting atrocities, albeit in a different form, are being repeated somewhere in the world right now.

Nourishment for those roots comes from every little incitement for intolerance, where displacement through scapegoating pedals a promise of purity and a promised land. Targets can be wide and varied - nationality, skin colour, religion, language, physical appearance, sexual orientation... Then there are targets who hold beliefs, values and attitudes that challenge the direction taken by their government - political rivals, trade unionists, strikers, campaigners...

It was the Jewish population of Europe that was the most systematically persecuted by the Nazi regime and its allies. More than six million Jews perished in a genocide programme that will stain humanity for all time, but the Holocaust saw many millions more consumed because of who, what or where they were.

That programme of extermination casts a shadow over all of us, proving that unimaginable cruelty can dwell in ordinary people, not monsters, and International Holocaust Day is a time to remember not six million, but 17 million.

That is the conservative total of all the victims in the death camps and concentration camps and other sites of horror. We remember the names of just a handful of these places - Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Dachau, Mauthausen-Gusen - but there were many more, hundreds and hundreds more.

While we may have forgotten about, or never even knew, the extent of that nightmarish network of man-made hell, we should not forget that along with the yellow Star of David there was a colour spectrum of triangles, all badges worn by those 17 million victims in what the Romani people term the Porajmos, the ‘Devouring’.

The reason I was prompted to write this was that just a few weeks ago I received an update from Holocaust archivists regarding my Polish grandfather. Nearly a century on there is still documentation surfacing, details emerging, and families seeking answers. These dedicated teams continue to expand 17 million stories and give so many tormented souls the remembrance they deserve, and bring them back into the light.

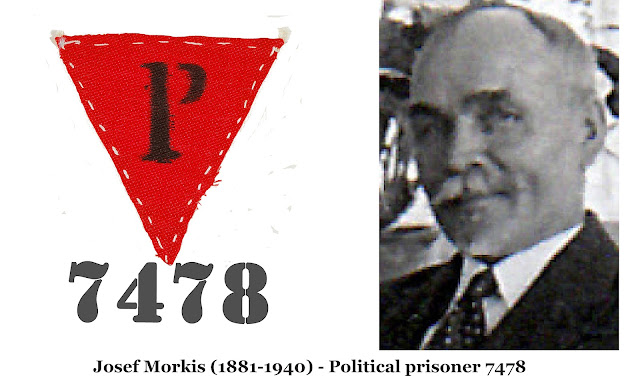

As a political prisoner, the badge worn by my grandfather, Josef Kaspar Morkis, was a red triangle.

He was persecuted as a Schutzhaft case. This was basically a Nazi ruling that dispensed with any legal hearing as immediate custody was decreed as appropriate as the offender was a threat to the state, or whose life was deemed at immediate risk within the Reich from those outraged by those opposing the Nazi regime. Whatever para-legal excuse was used, it was, invariably, a death sentence.

Josef was stripped naked and, with others, marched through town before being forced into a cattle cart bound for Dachau, Germany, in May 1940. This was the Nazi’s first concentration camp, opened in 1933 to house political opponents. In June, my grandfather, now prisoner 7478, was transported to Mauthausen, Austria, where on October 16, at 1pm, he was murdered. Josef was 59 years of age.

His story, tragic though it might be, is not exceptional. If he was classed as an “undesirable” his death was one of 70,000; if he was viewed simply as an unnecessary Pole, then he was one of 1,800,000.

In either case, these are horrific numbers. Where just one brutal, cold-blooded murder, committed for faith, or race, or nationality, or politics, or sexuality, or disability is repugnant, it is hard to comprehend the extermination of 17 million human beings.

The information I received about Josef from the authorities didn’t add anything to the story I already knew. It was entries in ledgers and transfer documents, but these were the first tangible pieces of evidence in his final weeks.

Perhaps, he was standing in a line in front of that administrative clerk who took his name, or called him out. Or his details were in a pile being processed by a camp secretary before her lunch. But to see that tidy handwriting, detailing a man’s life and determining his death, isn’t just an emotional experience, it is also a chilling one.

Those ledgers of names were books of lives, each precious, each cut short, and each with a story to tell.

So on International Holocaust Day, I won’t just be remembering the grandfather I wish I could have hugged just once, or even the 17 million ‘devoured’ by fascist ideology, but I will also remember those with pens and stamps who sanctioned prejudice, silenced protest, stopped strikes, suffocated opposition, and sanitised hatred.

While we should never forget the victims, we should also never forget those who willingly catalogued and created them, or those who quietly stood by and let it happen.

Nearly a century on, the question remains the same. Are you a badge giver, or a badge wearer?

No comments:

Post a Comment